On a sunny Monday morning in August 2018, a speeding car lost control and rammed into a group of people awaiting their bus. Several, including 8-months-pregnant Stephanie Johnson, were rushed to the busy Level I trauma center at University Hospital, where a team of doctors, nurses and technicians worked frantically to save them. As Johnson’s pulse stopped and her baby’s dropped, they were faced with a crucial, high-stakes, life-and-death decision – and there was no time to think.

“That day started off busy. At 7:30 we had our first Level 1 Alpha come in,” said trauma nurse Matt Lozano. A Level 1 Alpha is the highest-urgency classification possible for a trauma. It’s a case that’s serious enough to mobilize multiple specialty teams – anesthesiology, blood bank, respiratory therapy, pharmacy, X-ray and social work.

“Before 11 o’clock we had received five Level 1 Alphas,” Lozano said.

And that was just the warmup.

11:07 a.m.

The intersection of Zarzamora and Culebra is a multi-lane crossroads of heavy auto, truck and bus traffic, ringed by bus stops, convenience stores, gas stations, and pawn shops. The firetruck bays of the historic brown brick Fire Station No. 10 face it, and behind the fire station rise the golden domes of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Little Flower. The weather that morning was clear and warm. Stephanie Johnson, eight months pregnant, was waiting for her bus alongside several other commuters when a car speeding west on Culebra emerged out of the traffic and swerved. She saw it cross the intersection and lose control. It was heading straight toward the bus stop. Johnson began to turn away. The car hit an embankment and went airborne, plowing into the group, slamming into Johnson and several others. Horrified witnesses called 911. The units from Fire Station No. 10 were already out at another call. Dispatchers notified other nearby help. Emergency response vehicles raced to the scene.

MEDCOM, a regional trauma coordination center, began coordinating patient transfers for multiple injuries. University Health System’s radio room was notified by MEDCOM Incident Command and launched a Level 2 trauma team activation. Estimated time of arrival for the first patient was three minutes. Cassie Rubio, a PA in the trauma department, immediately called Dr. Deborah Mueller, the trauma surgeon in charge. Dr. Mueller was finishing up a surgery in the OR upstairs. She prepared to head down to trauma, a process that would take her four minutes. Then things heated up even more. One minute after the Level 2 activation came the morning’s next Level 1 Alpha activation, with a five-minute ETA for a very badly injured, pregnant patient – Stephanie Johnson. Instead of five minutes, she arrived in two.

11:37 a.m.

Patient arrives.

Rubio, Lozano and a phalanx of multi-specialty trauma doctors, nurses and staff were already at work in the Trauma Resuscitation Unit. The TRU is a large bay where the most critical patients are cared for. It normally holds four patient beds. That morning, there were already six patients in there, and two were Level 1 Alpha. Johnson made seven. When she arrived, she didn’t look good.

“She was gray,” Rubio said.

“Her eyes were huge,” Lozano said. “I thought, ‘This patient is going to die.’”

Dr. Mueller took the critical care elevator down from the OR. It has no stops and opens a short walk from the main trauma bay. She rounded the corner and saw a very full and very busy room. She did a quick assessment.

11:40 a.m.

“I didn’t know who’s old and who’s new,” she said. “I immediately recognized that I needed to call for help.” She messaged Dr. Douglas Pokorny, a second-year trauma and surgical critical care fellow: “Several level 1 now.”

“When trauma needs reinforcements, ‘we call it ‘loading the boat.’”

That particular boat was getting very full when Dr. Mueller arrived. It was crowded with doctors, residents, nurses, and techs. There were some first responders who wanted to see their patients pull through. Rubio was with the group around the head of Johnson’s bed, talking to her and trying to get a response. Dr. Mueller checked Johnson’s femoral pulse, high on the top of her thigh. But then she stepped back and watched the teamwork.

“It’s kind of like I’m a conductor,” she said. “I don’t really get to play an instrument here.”

11:41 a.m.The team intubated Johnson. The Obstetrics team arrived.

11:44 a.m.

Dr. Lauren Javernick, a second-year OB resident, was monitoring the baby’s heart rate, which was in the normal 140 bpm range. At the same moment, the trauma team got another Level 1 Alpha alert – another critically injured patient was on the way to the hospital with a five minute ETA.

The stakes were skyrocketing by the second.

11:45 a.m.

Dr. McCroy holding baby Ethan.

Dr. Georgia McRoy, a third-year emergency medicine resident, was doing an assessment on Johnson when the mother’s heart stopped.

McRoy went on autopilot and started CPR.

Trauma nurse Amber Hicks, one week back from maternity leave, was not on shift that day. She had been in for a meeting and knew they were busy in TRU. She entered the room as Dr. McRoy started chest compressions.

11:46 a.m.The fetal heart rate dropped to a dangerously low range of 80 bps.

Porkony yelled, “I need a combo tray and a thoracotomy tray! Somebody get me a knife! We are going to do a C-section and a thoracotomy.”

One team member said, “We need to go to OR.” Pokorny said, “We don’t have time.”

Normally this would be where the team made the call to save either mother or baby.

“The normal teaching is to try to get mom back, and if you don’t get mom back in four minutes you save the baby,” Pokorny said. “We had enough people that we could do multiple things, and I already had evidence that he (the baby) was in trouble.”

Hicks said, “You never say ‘I want to save the baby over the mom,’ but at that point, the baby had a pulse.”

Dr. Pokorny turned to Dr. Mueller and said, “Both?”

“Both!” she said.

11:47 a.m.

The team administered epinephrine to Johnson to help with bleeding control.

Trauma nurse Matthew Lozano handed a blade to Dr. Pokorny so he could make the incision for the C-section. He made a fast decision to do a horizontal, not vertical, cut. “If her liver is exploded and I open her up on the midline, she bleeds out and she dies,” he said.

As soon as that cut was made, Dr. McRoy stepped back from Johnson and Dr. David Bittenbinder, a first-year trauma fellow, stepped up. He used another blade to make the horizontal cut between two ribs. He opened up the space between Johnson’s ribs with a retractor to reach her heart. A broken rib had punctured it, and blood had filled the pericardium, the sac that surrounds the heart. The pressure was choking off the heartbeat. Dr. Bittenbinder nicked open the sac with the blade, releasing much of the blood that was suffocating her heart.

11:48 a.m.

After Dr. Pokorny’s initial incision, Dr. Javernik stepped in to complete the delivery, cutting open Johnson’s uterus. In less than a minute she was handing the baby to Dr. McRoy. Dr. McRoy set the infant on the bed at his mother’s feet – still attached by the umbilical cord – and rhythmically compressed his tiny chest with her fingertips.

“He was the grayest baby I had ever seen,” Dr. McRoy said. “I knew he was dead, so I just started CPR.”

Hicks said, “One patient turned into two patients that were both coding.”

It probably took another 30 to 40 seconds to get the clamps and cut the cord. Dr. McRoy handed the baby to Hicks. Hicks moved the baby to the warmer. McRoy, joined by members of the pediatric transport team, kept working to save him.

11:49 a.m.

Dr. Pokorny cleared out the rest of the blood in Johnson’s pericardium, working out a heavy clot that had formed inside of it.

Dr. Bittenbinder took her heart in his hand and massaged it three times until it began to beat on its own. The mother came back to life.

“We scooped the clot out of the chest and it was time to go to the OR,” Dr. Pokorny said. They covered her chest but left the retractor in place, keeping the heart exposed for the short trip from trauma to the OR.

“It’s super useful to be able to see if the heart stops again,” Dr. Bittenbinder said.

11:50 a.m.

Johnson was rushed up to the OR for further surgery. The neonatal intensive care team arrived to take over Baby Ethan’s care. OB fellow Dr. Alejandro Peña was able to intubate him. Dr. Amy Quinn, NICU assistant medical director, put a line in the infant’s umbilical cord. They gave him saline and medication.

“Once he was stable-ish and had a little bit better heartbeat, we transported him up to NICU,” Hicks said.

There were other doctors and nurses and staff and patients in the bay and more were coming. But for the team working on those patients, what had been a handful of hectic minutes expanded and slowed until the image of mother and child was etched permanently in each their minds.

“I looked up and I couldn’t believe that hardly any time had passed,” Rubio said. “Time was really compressed.”

McRoy sat down. “My hands were just shaking,” she said. “She was 28 and I’m 28.”

Hicks was all nurse as she helped get baby Ethan to the NICU. When that was done, and she had walked back to the elevators, she became a mother with her own tiny baby at home, and she cried.

“He was blue, he didn’t have a great pulse, he had been receiving cardiac drugs,” she said. “I just delivered this baby that I don’t think is going to live, and – how do we tell Stephanie?”

Pokorny had gone to the OR to with Johnson.

“After the operating room, I went straight to the NICU to check on Ethan,” he said. “It was really seeing him alive that kind of let me have that moment” to decompress from the tense scene. “Even at that, for two or three days I replayed everything in my head.”

It was a dramatic and unusual case where the odds were strongly against mother and child.

The survival rate for blunt traumatic cardiac arrest is 1 to 2 percent. For babies delivered by C-section after the mother has died or is dying after blunt trauma, the survival rate is unknown. But it’s 20-30 percent for babies delivered by C-section from dying mothers in non-trauma situations.

The physicians have found one other case from the 1980s where a mother and child both survived a thoracotomy and emergency C-section, Pokorny said, but that was not a trauma case.

The entire team kept close tabs on the progress of mother and child. Johnson was awake by the next day and began a speedy recovery despite multiple painful injuries and a cardiac arrest that few survive. The NICU team gave Ethan a transfusion and cooled his body temperature, which can help reduce brain injury. The practice is to keep the body several degrees cooler than normal temperatures for three days. Only after slowly warming the patient can the medical team get a good read on how he was doing.

“We were ecstatic when we learned that Ethan was warmed and doing well,” Hicks said.

Along with the incredible personal journey the physicians and staff took with Johnson and her baby, they were also solidified and transformed as a team.

The team now has a heightened awareness when a pregnant patient comes into trauma and is using the event to examine what went right and what could be improved.

“The group of us that were involved that day, we certainly have a bond,” Pokorny said.

“Because of this, we’re going to do mock drills with Trauma, ER, OB and us,” Quinn said.

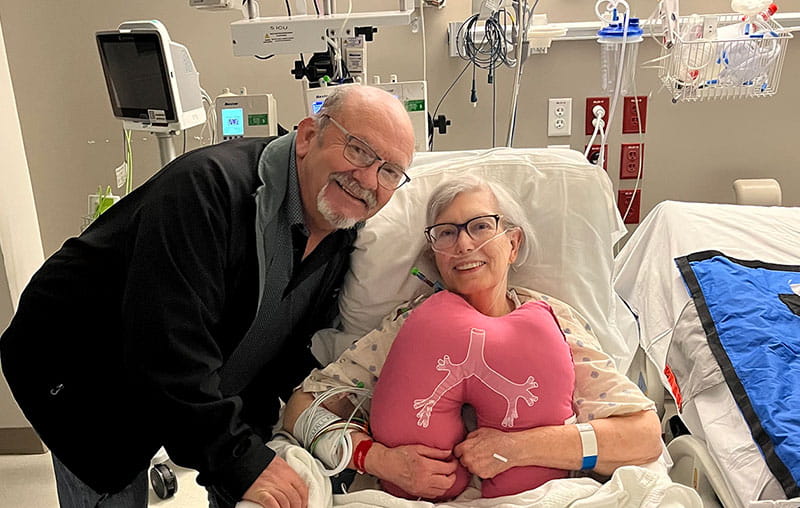

They also did a multi-team presentation at the May 2019 trauma conference held by Southwest Texas Regional Advisory Council. Johnson and baby Ethan – who at nine months was hitting all his developmental milestones – were special guests. Both patients got to meet the first responders who first cared for them that fateful day, and everyone was delighted to see their progress. They crowded around him and took lots of photos, and he seemed to enjoy the exchange as much as they did.

“Every time we said his name in the talk, he cried out,” Pokorny said. “He’s a happy little baby.”

*Baby Ethan has since been diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy, said neonatologist Dr. Alice Gong, medical director of the University Health System PREMIEre Program. Ethan is receiving care through the PREMIEre Program that will monitor and help his development. “It’s amazing he’s done as well as he has,” Dr. Gong said. “You don’t have that period of anoxia and not get away without some damage.”